Is it Helpful to Score Countries on their Progress in Food and Nutrition?

In recent years, a number of new indices have sprung to life that rank countries based on their progress in improving food systems and nutrition outcomes. Among these are the Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index which scores governments on their political commitment to tackling hunger and the annual self-assessments on progress in meeting four strategic objectives for improving nutrition, carried out by countries in the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement. These efforts, which are focused on undernutrition, systematically examine evidence of progress and share a common goal: to hold governments and others to account. But is this helpful and does anyone take any notice?

At an event held on 10th February 2016 in London convened by the Food Foundation, three mechanisms for accountability were presented, which are useful in settings with high rates of overweight and obesity. First, the Food Environment Policy Index (Food EPI) was introduced by Professor Boyd Swinburn from the University of Auckland. The index takes stock of existing policies that govern the food environment of a country and compares these with international examples of best practice. Second, the Global Nutrition Report was presented by Professor Lawrence Haddad. It tracks 80 nutrition indicators for all countries of the world allowing the UK to be compared to its neighbours and thus build accountability. Third, the Access to Nutrition Index was presented by Inge Kaur. This index ranks 22 of the largest food manufacturers on the extent to which they are supporting good nutrition outcomes.

These accountability tools are important because they help to shift discussion from responsibility pledges to accountability systems. This is particularly relevant in the UK where the Public Health Responsibility Deal is the major mechanism of influence over the food industry.

The mechanisms also foster collective agreement and action. A strength of both Food EPI and the Global Nutrition Report is that independent experts are brought together to collectively review the evidence and identify priority actions so building a stronger consensus based platform for action.

A further strength is the scope for inter-country comparison. The UK, for example, was shown to have the highest level of adult overweight and obesity in Europe standing at 63% and the worst rates of exclusive breastfeeding in the world. Missing data remains a problem, however. The UK currently does not provide data for four of the six global nutrition targets agreed by the World Health Assembly for 2025, even though it has signed up to these targets and will be required to report against them as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite this, the role of the UK as a world leader on public actions for healthier food environments was stressed. The UK is leading the way on areas such as school food standards and these positive examples should be celebrated.

This event was important for bringing together academics and civil society working on undernutrition, on the one hand, and obesity on the other. The need to shift towards addressing malnutrition in all its forms was underlined. The upcoming Rio Olympics summit on nutrition in August 2016 is a great opportunity to secure commitments for nutrition. For the UK government, this means making commitments to improve nutrition at home as well as abroad (see What will the UK’s commitment to nutrition be at Rio? (And I’m not talking about DFID)

But are these indices helpful and does anyone take any notice? The Access to Nutrition Index appears to be having some impact. While some companies respond well to the scores and some don’t, investors and investment advisors are beginning to pay attention to the score and factoring it into their investment decisions.

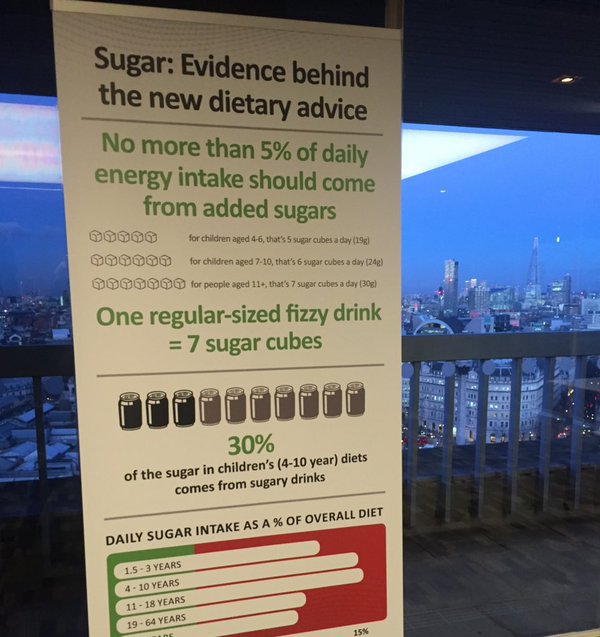

There is also scope for influencing UK government decisions. The Food Foundation is in the early stages of applying the Food EPI and collective agreement on the critical gaps in current UK food policy could be a powerful tool of influence in advance of the publication of the new Childhood Obesity Strategy now due to be published in the summer. There are moves afoot to build a Parliamentary Network to share international experience of food and nutrition systems. The Network will start with meetings between Brazilian and UK Parliamentarians with a view to strengthening commitments at the Rio summit.

The major take-away from the event was that accountability mechanisms are helpful in systematically reviewing the evidence and ensuring that governments and others are made accountable for the goals and targets to which they have signed up. The collective process involved in the development of indices is itself helpful for securing agreement on priority actions while highlighting examples of good practices.